For decades, neurodivergent students — those with ADHD, autism, and other learning differences — have been expected to conform to rigid school norms.

Sit still.

Make eye contact.

Show your work.

But what if these expectations are doing more harm than good? What if the true foundation of learning isn’t compliance, but belonging?

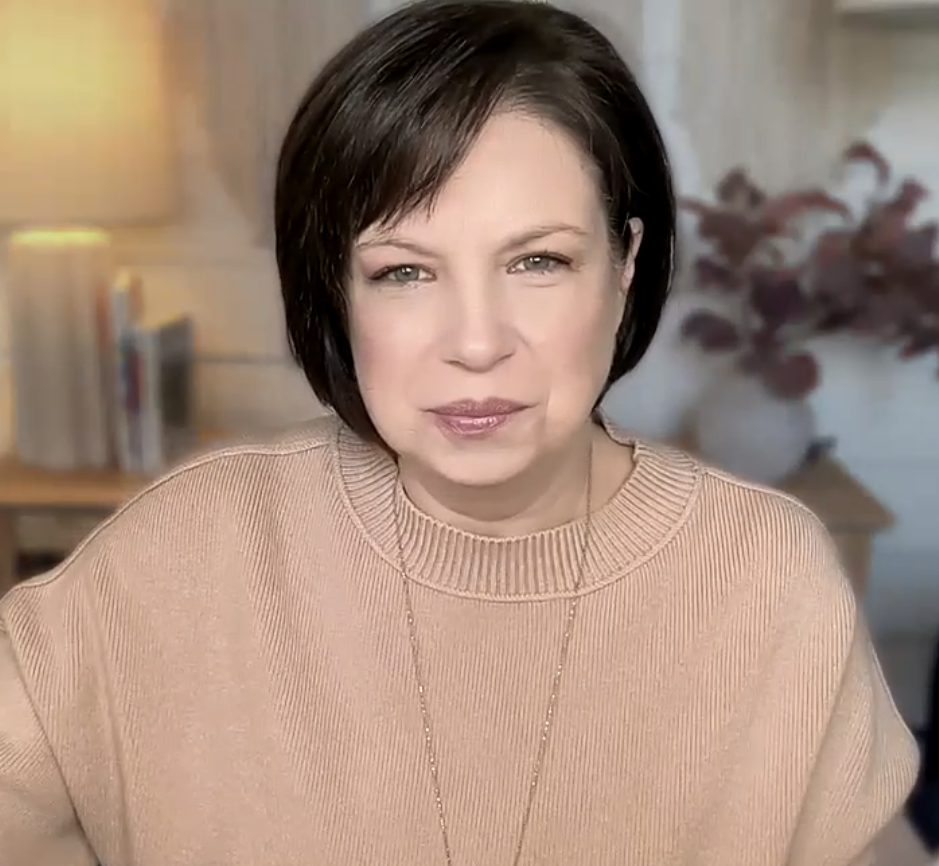

In a powerful conversation with educator and author Amanda Morin and licensed counselor Emily Kircher-Morris, the message was clear: if a child doesn’t feel safe, they can’t learn.

“A neurodiversity-affirming school feels like belonging,” Morin said. “It’s a space where students don’t have to mask who they are to be accepted. They’re supported, not judged, for the way they show up.”

Morin and Kircher-Morris co-authored Neurodiversity-Affirming Schools: Transforming Practices So All Students Feel Accepted and Supported. In the book, they explore how educational systems can move beyond traditional inclusion and toward deep, systemic change.

“Fitting in is not the same as belonging,” said Kircher-Morris. “Fitting in requires you to change who you are. Belonging means you’re accepted just as you are, with all your strengths, quirks, and needs.”

The conversation highlighted how schools often misinterpret behaviors rooted in dysregulation or sensory overwhelm as defiance. The result? Shame, exclusion, and trauma for neurodivergent kids.

“Hypervigilance uses up all the brain space a child needs to learn,” Morin explained. “If they’re constantly wondering, ‘Am I okay here?’ there’s no room left for math or reading.”

This isn’t just theoretical. Morin and Kircher-Morris are both neurodivergent and raising neurodivergent kids. Their insights are grounded in both personal and professional lived experience.

They also point out that when kids aren’t given flexibility, autonomy, and support, they internalize harmful messages about their worth. And it’s not just students who carry the weight. Many teachers enter the profession with their own unexamined experiences, often repeating harmful disciplinary patterns simply because they don’t know another way.

“Teachers need emotional competence just as much as students do,” said Morin. “Self-awareness, self-regulation, and the ability to reflect — that’s how you model what it means to be human.”

So, what does it take to build a neurodiversity-affirming school?

It starts with asking better questions: Why do we expect this? Is it truly necessary? Is there a different way this student can show what they know?

It means honoring student voice and special interests, creating multiple paths to success, and ditching one-size-fits-all rules that fail to account for developmental trauma and nervous system sensitivity.

Perhaps most of all, it requires humility.

“You don’t have to have it all figured out,” said Kircher-Morris. “But you do have to be willing to grow.”

As schools across the country reckon with how to better support all learners, this conversation offers a hopeful path forward, one that values authenticity over conformity and connection over compliance.

And maybe, just maybe, that’s the kind of classroom where real learning begins.