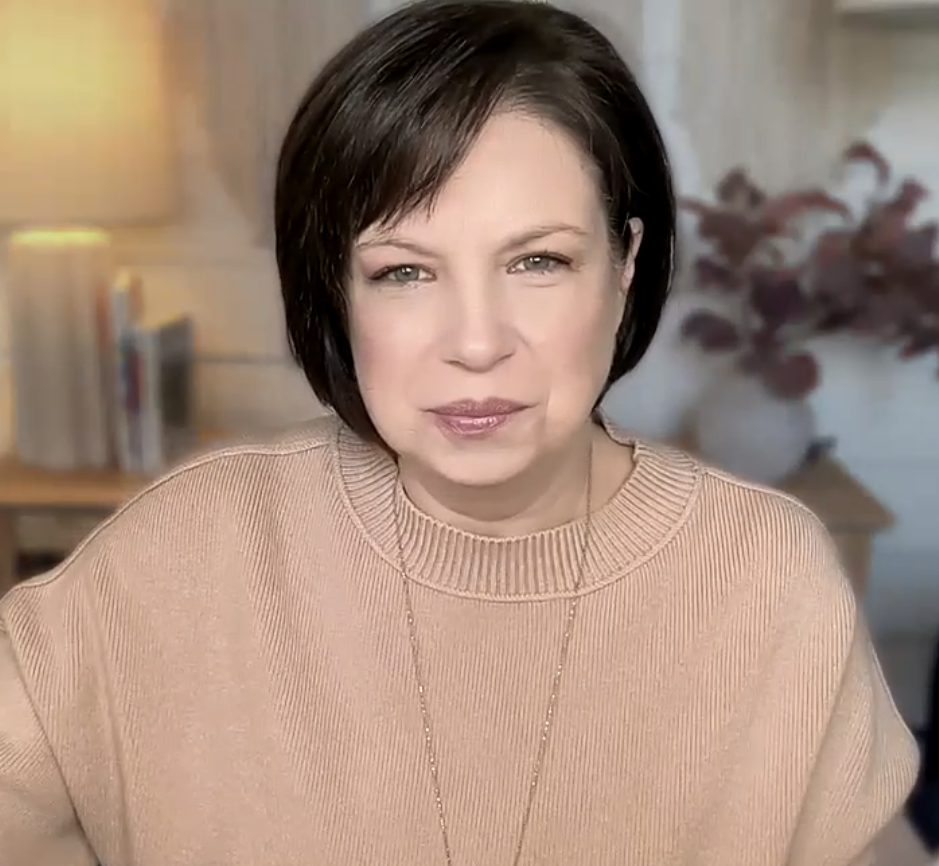

Julie King is the author, along with Joanna Faber, of the new book, How To Talk When Kids Won’t Listen, as well as the best selling book, How To Talk So Little Kids Will Listen, which has been translated into 22 languages worldwide. Julie and Joanna created the companion app, HOW TO TALK: Parenting Tips in Your Pocket, as well as the app Parenting Hero.

Julie has been educating and supporting parents since 1995. In addition to consulting with individual parents and couples, she speaks and leads workshops online and in-person for schools, nonprofits, businesses and parent groups across the U.S. and internationally. Julie received her AB from Princeton University and a JD from Yale Law School. She lives with her husband in the San Francisco Bay Area where they are visited often by her three grown children.