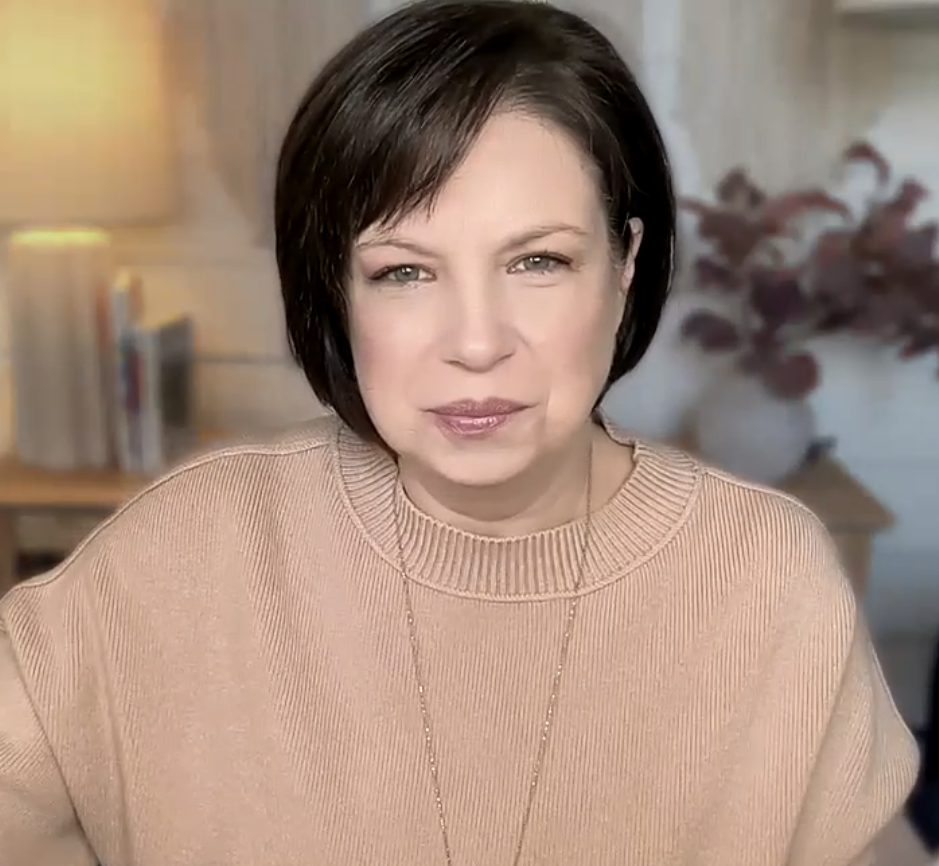

Get some clarity.

This isn’t junk mail… this is life mail. These are strategies for your real life. My newsletter, Clarity, gets delivered to over 30,000 people each week to help them get clear on how to be the parent your neurodivergent kid needs. I’d love to help you, too. Subscribe now, it’s free.